photography is more than a pretty picture

Roasting coffee in Addis Ababa, October 2012.

I took this photograph more than a decade ago in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I’ve always loved this photo because it captures a moment in time that looks exactly like what it felt like to be there. I hope, when someone looks at this photograph, it sparks their imagination. I hope they wonder what it felt like to witness what I was witnessing: they imagine what the air smelt like, the smoke mixing with the scent of the roasting beans. I hope they wonder what made me stop to take the photograph — was it the aroma? Was it the light moving through the smoke? I hope they notice that the young woman in the image is speaking, with a soft smile on her face, and wonder what she’s saying: perhaps she’s explaining the process of roasting the perfect beans. Perhaps she’s describing her life, or sharing details about her family. Perhaps she’s just being neighbourly to this stranger — me — with the complicated-looking camera in her hands. I hope they wonder what became of this woman over the last ten years. I hope, if the person looking at this image is Ethiopian, they feel a pang of recognition. Of patriotic pride and affection. If the person looking at this image isn’t Ethiopian, I hope they become curious about traveling to the country. I hope they want to learn more about its people. Its culture.

I hope, when someone looks at this photograph, they are transported to that moment in time, and they feel a connection with the woman in the image, and with me, for sharing this experience of being there.

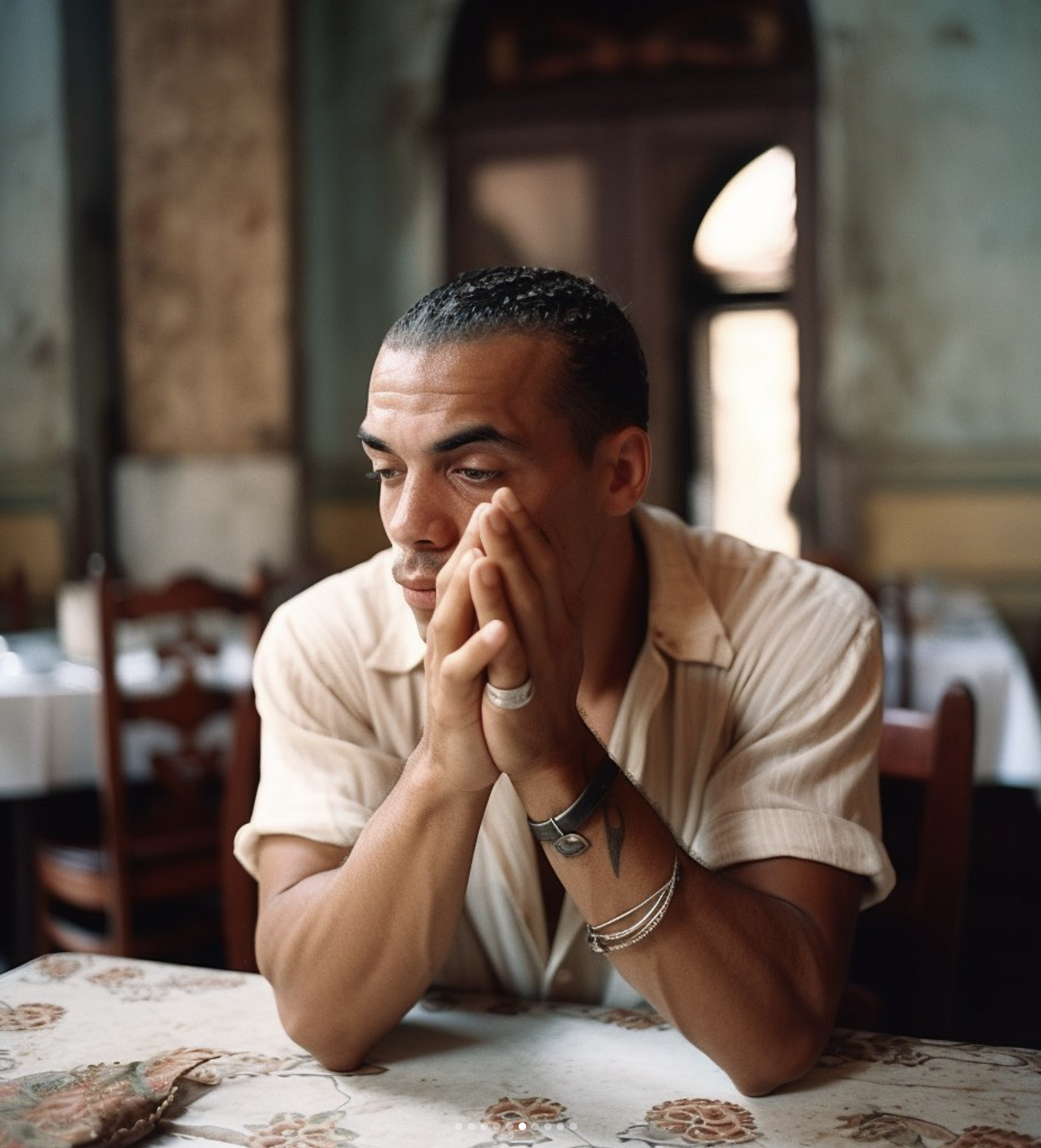

Created by AirLab.

This image, on the other hand, isn’t one I took. In fact, it isn’t one anybody took. And in another fact, the man in this “photo” — as pensive? melancholy? as he appears — doesn’t exist, either. This image was created with artificial intelligence, as part of a project by AirLab, exploring historical events and realities of Cuban life that have, since 1961, motivated Cubans to cross the 90 miles of ocean separating Havana from Florida.

Now admittedly, this is a beautiful image. The light is perfect. The photorealism is astonishing. But is it just me, or do you also feel a bit betrayed, now that you know that this image isn’t actually a capture of a real moment in time? If I were to hazard a guess, I would say that the betrayal comes from more than the simple fact that we assumed the image was created by a person behind a camera and it wasn’t. I think the reason we feel betrayed is because a computer-generated image denies us an opportunity for connection with a real person, or to a true story behind the image. In this case, maybe even to Cuba itself.

And this betrayal of experience and connection? This is the reason that there are forms of AI that make me deeply sad. I’m not talking about the silly uses of AI, like those that imagine entertainer John Oliver marrying a cabbage. I’m not even talking about the problematic forms of AI stealing the work of bonafide artists, without any credit (although that is admittedly a severe problem). I’m talking about the use of AI potentially manipulating our ability to connect with people and places — real people and places. I’m concerned that in an age of “fake news” and the continued eroding of our interconnection, when we can’t trust the images that we see as authentic, we’ll only become even more disconnected from each other. And I don’t know how we heal the ills of the world — the bigotry against people who are different from us, the misunderstandings, the inability to take care of each other — without true connection.

Now, I’m not sure what this means; after all, the AI train has left the station. As time goes on, the quality of the photorealism of these images is only going to continue to get better and better, perhaps outstripping even the very best of photographers. But I hope that this does not deter folks from taking and making photographs. In fact, I hope we do it more than ever, When cameras became ubiquitous on every phone in every back pocket, I cheered — because the ability to share real stories and create connection had been democratized. I hope we all never forget that power.

And I hope we continue to take and share our stories, creating as much connection with each other as we can.

the art of noticing